NEWSLETTER

|

From the Class of ’92: “We worked for Frank”

By Radhika Balakrishnan, Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos, Natalia Kanem, Anthony Romero and Marcia Smith

We were part of an especially large and diverse class of new program officers starting at the Foundation in 1992. We met on the first day of orientation and remain lifelong friends. We write now to pay joint tribute to the man who helmed the Foundation during the early part of our tenures, a man who mentored us, inspired us, taught us and made us proud to be a part of the collective endeavor called the Ford Foundation.

None of us had met Frank Thomas when we showed up for work on our first day. We were hired across five programs, with various hiring managers involved and with Susan V. Berresford, Frank’s right hand and remarkable successor, serving as the final sign-off on our joining Ford’s ranks.

We knew him first as Mr. Thomas. Most often and most importantly, we knew him as “FAT”, as we directed our RGAs (recommendations for grant authorization) to him, via “SVB” and our respective directors. It was clear, in this and so many other unspoken ways, that he was in charge. He was our audience of one.

Each of us was drawn to Ford’s mission and history, its commitment to causes, issues and institutions that had animated our early careers. But in all candor, we also came to work for Frank Thomas. By reputation, he led the Foundation courageously and with such distinction across a wide range of disciplines.

As young professionals of color, we felt especially proud that the largest and most impactful foundation at the time was led by a brilliant, dignified and visionary Black man with a wide breadth of experience and expertise. We showed up in the fall of 1992 to play on Mr. Thomas’ team and we were proud of our jerseys. Over time, we would come to love our teammates.

As our confidence grew and we all received promotions at different times, we got to know him better. We got to spend more one-on-one time with him, and even ascended to new-found status in being able to call him “Frank”. The days after successful board meetings, the holiday parties and lunches at the big table in the 11th floor cafeteria that Frank normally occupied were moments to relish in the casual Frank.

Every bit as distinguished, insightful and visionary as Mr. Thomas, the Frank we came to know was also warm, nurturing, mentoring and funny. He had the best smile. In program officers’ meetings, when one of us was presenting an especially significant grant, and when others in our class would jump in with words of support, Frank would crack a grin and signal that he knew precisely what we were up to.

Radhika Balakrishnan, as part of the Asia Regional and the Reproductive Health Programs, notes that Frank supported the program’s global focus of reproductive health and rights that had a major impact on the outcome of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development at the United Nations.

Radhika had the privilege of working with Peter Geithner, one of the few Republicans at the Foundation, and José Barzelatto, a Chilean exile from the Allende government. With Frank’s encouragement, Peter and José worked together to hire some of the strongest feminist program officers in the Asia program.

Even after leaving the Foundation, Radhika consulted Frank on her early work on human rights and economic policy, demonstrating that his mentorship went beyond employment at Ford. Frank truly wanted us all to succeed wherever we landed. He was interested in who we were. While Frank knew the most important people in the world, Radhika remembers that he made his younger staff members feel as equally important to him as the heads of state, dignitaries or world leaders he knew.

Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos developed a very meaningful rapport with Frank as she developed her New York-based program. She was a Pakistani-American immigrant set to replace the traditional foreign policy experts who had long managed Ford’s United States foreign policy portfolio. Shep Forman, her director, became her program’s most valued compass. Mahnaz was charged with and committed to bringing greater racial and gender diversity to the influential institutions of the foreign policy establishment and broadening their research and studies agenda after the end of the Cold War.

Under Frank’s leadership, the Foundation had made enormous inroads in diversifying the boards and staffs of its domestic policy grantees, while the foreign policy institutions, many of which also had powerful memberships, lagged significantly behind.

Mahnaz had Frank’s essential support as she negotiated challenging grants to diversify both research and personnel at these foreign policy institutions, and broadened the playing field by growing new institutions and nurturing pipelines for racially inclusive and women scholars in international foreign and security policy.

Frank well understood the delicate dynamics of trying to create change in independently powerful institutions and it was Mahnaz’s job to properly represent the Foundation in this mandate. When Mahnaz developed the worldwide Varieties of Muslim Experience meeting in 1994, which explored novel themes of work for the Foundation, Frank was also a stalwart supporter, encouraging open minds at the Foundation.

Natalia Kanem was hired into an office that was very near and dear to Frank’s heart, the Lagos field office. First as program officer for reproductive health and rights, and then as Representative for West Africa, Natalia remembers Frank’s interest in and commitment to that country’s efforts to chart a new course for its people. She recalls Frank’s charge to her: steady the Nigeria program. Her mandate was “to stay and deliver” during the dictatorship period in the 1990s when almost every donor group except Ford fled the country.

The Foundation, through the frequent visits of Ambassador Donald McHenry, helped to ensure the safety of General Olusegun Obasanjo, a Foundation Trustee who eventually became President of Nigeria, during his imprisonment. Even in times of crisis and challenge, Frank was big on structure and accountability, and he insisted on essential safeguards against corruption and misconduct to ensure the integrity of the Foundation’s work.

Of course, Natalia notes that Frank’s commitment to Nigeria built on his earlier work to support human rights and a democratic transition in South Africa. Through the weight of his intellect and towering reputation, Frank positioned the Foundation as the leading external force to support the end of apartheid. Frank’s book on South Africa, Time Running Out, was hugely influential. It is still on Natalia’s bookshelf as a reminder to her, now as head of UNFPA, the UN sexual and reproductive health agency, to use whatever creativity she can muster to innovate and improvise in the push for sexual and reproductive rights.

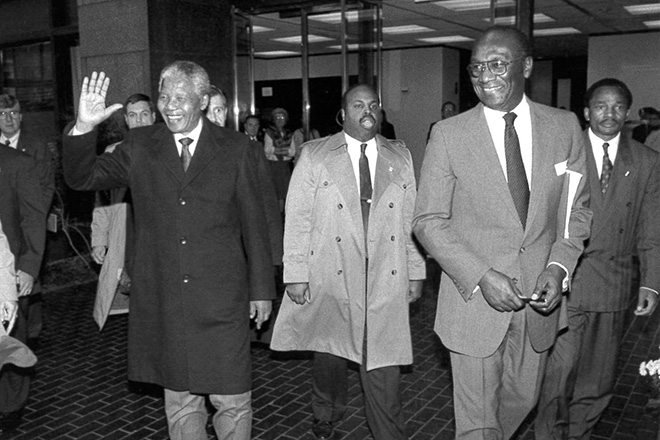

Frank’s personal relationship with Nelson Mandela is legendary, but he was also close with Mamphela Ramphele, Albie Sachs and Archbishop Desmond Tutu among many other visionary South African leaders. Through some of the most important years of the Foundation’s engagement with South Africa, Frank’s leadership bolstered the anti-apartheid movement and provided the scaffolding for dialogue between figures in the Afrikaner government and the African National Congress. Later he did the same to assist in resolving differences among other groups within South Africa.

Anthony Romero was also hired into a post that Frank Thomas kept a close eye on: the civil rights portfolio. Anthony was 27 years old when he was hired to manage a portfolio that was mission critical to the Foundation’s persona. Ford had helped create many of the nation’s leading civil rights organizations: the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the National Council of La Raza.

Frank’s dear friend and Ford Trustee, Vernon Jordan, had headed the National Urban League. Civil rights issues were top-of-mind for Frank, Vernon and the Foundation.

Frank had engaged and promoted a remarkable civil rights attorney, Lynn Walker Huntley, to direct his Rights and Social Justice Program. With Lynn at his side, Frank oversaw the creation of a Black Church Program to assist with the secular service delivery of African American churches. They deepened the Foundation’s engagement with the Native American and Latinx communities. They also expanded this work to include Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), exploding the myth that the AAPI community was a “model minority” that should go it alone.

And when the NAACP came under duress and neared collapse, Frank and Lynn together intervened to provide financial and technical assistance that would ultimately put the organization on a course for greater strength. The fact that the NAACP now celebrates its 111-year anniversary under the remarkable leadership of Derrick Johnson has everything to do with Frank’s willingness to deploy his team and his Foundation’s resources and reputation to help buttress one of America’s greatest treasures.

Marcia Smith was Lynn Walker Huntley’s choice to anchor the Foundation’s efforts to support the professional development of minority elected and appointed officials. Marcia came to the Foundation after serving as New York City Mayor David Dinkins’ Chief of Staff. Under Frank’s leadership, Marcia expanded the Foundation’s national work in voter engagement and voter education, as well as its work to strengthen democracy through media policy reform.

Frank and Lynn’s groundbreaking work to provide philanthropic support for seminal films, such as the documentary series “Eyes on the Prize”, inspired Marcia’s award-winning career in documentary film over the two decades since she left the Foundation. And when she stepped back into philanthropy at another foundation, Frank once again provided steady advice and counsel.

The sweep of Frank’s leadership across geographies, issues and institutions over his 17-year tenure as President of the Ford Foundation had a profound impact on the trajectory of peace, justice and human dignity in the United States and around the world. Yet as these personal anecdotes and reflections demonstrate, perhaps Frank’s greatest legacy is his influence upon the people he touched and the leaders he supported and mentored.

It’s been decades since any one of us worked at the Foundation. We have gone on to start and lead nonprofits, businesses and inter-governmental agencies. In all these efforts, while making our share of mistakes, whenever we have succeeded it has been because we channeled the best that Franklin A. Thomas taught us.

Whatever our future accomplishments, we still consider it one of our greatest honors to be able to say that “we worked for Frank.”

_______________________

LAFF Remembers Franklin Thomas: Co-Presidents’ Reflections by Suzanne Siskel and Betsy Campbell

He Left the World a Better Place by Susan Berresford

A Man of “Vision, Tenacity and Dignity” by Barron “Buzz” Tenny

Celebrating the Remarkable Legacy of Franklin Thomas by Darren Walker

“A True Humanitarian” by Shepard Forman

From the Class of ’92: “We worked for Frank” by Radhika Balakrishnan, Mahnaz Ispahani Bartos, Natalia Kanem, Anthony Romero and Marcia Smith

Grantees: “Up Front and in the Center” by Charles Bailey

Taking Risks “Is What We Do” by Steven W. Lawry

A Leader With “Vision and Courage” by Barry D. Gaberman

Forging “New Paths on Multiple Fronts” by Judy Barsalou

“The Tallest Tree in Our Forest” by Akwasi Aidoo

|