SPOTLIGHT

|

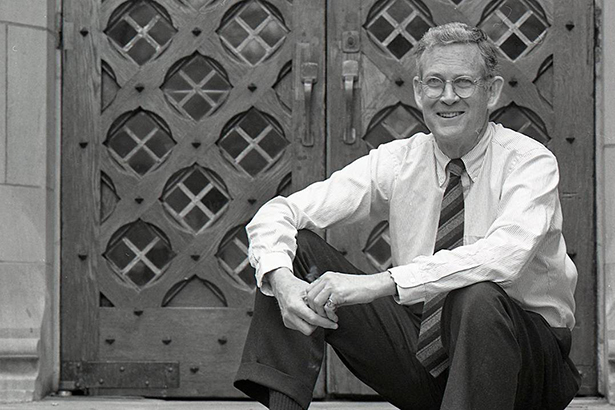

Remembering Craufurd Goodwin By Arthur I. Cyr

EIA was the smallest office in the old International Division, which was the largest in the Ford Foundation at that time and headed by David Bell, who was the strongest executive in the organization, though there was never any doubt that McGeorge Bundy was in charge.

Internally, we were widely regarded as rather effete and definitely “different”, since we were not directly or heavily involved in economic development work in the Third World.

There were rumors that our days were numbered, which Craufurd shared with me, though I never saw any hard evidence this was the case. Dave Bell was demanding but also always supportive, and a remarkably insightful as well as skillful manager. Frank Sutton took a particular interest in our work, and Craufurd referred to him as our “Guardian Angel”.

Craufurd from early on operated with great effectiveness to preserve and expand EIA, through imaginative programming and internal fundraising. Not surprisingly, he was strongly interested in Canada, and secured an appropriation to support work on Canada in Canada. The Foundation records had useful material showing characteristic U.S. condescension toward Canada, including a memo from years earlier suggesting the Ford Foundation treat the country like Puerto Rico!

Craufurd’s disciplined approach was instructive, especially during my last year at the Foundation when I worked part time for the looser Public Policy Committee.

He also secured an important appropriation to study the profound changes in the international economic system immediately after President Nixon’s dramatic decision to end Bretton Woods’ fixed-exchange rates. He was extremely positive about the productive Brookings Institution, and Henry Owen and Fred Bergsten were involved initially, dovetailing with the Foundation’s generous support of the Brookings Foreign Policy Studies program. The economist William Branson of Princeton then oversaw the work on a part-time basis. After the Trustees approved the initiative, Robert McNamara put his arm around Craufurd and gave him a hug. Big Bob did not give out many hugs.

We cut off many existing grantees, and Craufurd developed a project competition advertised nationwide to universities above a certain size, with submissions evaluated by external experts and winners chosen by a small committee. Alessandro Silj initially did the work followed by yours truly, after he moved on. We developed interesting new grantees, but an enormous amount of work was involved. Bundy made that point at an Officers’ meeting approving grants to the winners, while staring at me.

Craufurd secured yet another imaginative appropriation for “Two Keys” projects, where our office would cooperate with at least one other in making a grant. That could build on the more informal network of his predecessor, Howard Swearer. But Two Keys was not particularly active, at least during my tenure.

Craufurd once alluded to contacts with the Rockefeller Foundation, but did not mention details. I am sure his Ford Foundation experience was helpful in later administrative posts at Duke, especially in planning and handling details quickly, and in teaching effectively.

I am grateful to Craufurd for interviewing and recommending hiring me. The U.S. Army was breathing down my neck but I did not know exactly when or for how long. That was a time of hostility, in fact intense hatred of our military. I experienced that hate firsthand, including at Harvard, in disturbing ways. Craufurd and Frank were flexible, supportive—in fact, reassuring. Frank mentioned service in World War II was in some ways less difficult.

My mother-in-law was stricken with terminal cancer soon after I came to work and, in the face of pressing work, Craufurd went out of his way to find things for me to do in Southern California so I could help on the home front. I remember that courtesy most clearly.

We are fortunate to have worked at a major foundation where integrity was self-evident and conflict of interest prohibited. Obviously, our country needs that sort of example more than ever, in government as well as business.

Arthur Cyr, who worked at the Ford Foundation from 1971 to 1974, is director of the Clausen Center for World Business at Carthage College in Kenosha, Wis.

|