NEWSLETTER

|

Shep Stone and “Unintended Consequences” By Willard J. Hertz

My involvement with Andy—it was on a first name basis—began with my study of economics at Harvard University in 1942. Andy, then a graduate student from Greece, was my instructor in elementary statistics. I was facing the draft, and Andy worked after hours with me so that I could get credit for his course.

1948: I was hired by The Minneapolis Tribune as a reporter on business and finance, and he was on a tenure track in economics at the University of Minnesota. A brilliant economist, he was helpful to me on a number of stories. Further, my wife Stevie and I saw Andy and his wife socially.

1958: I joined the Ford Foundation staff as a writer in the Office of Reports, and Dick Magat assigned me to write a booklet on Ford fellowship programs. To interview a Ford fellow, I flew out to the Berkeley campus of the University of California where Andy was now a full professor, a widely published economist and chair of the economics department.

I dropped into his office to say hello, and he left a staff meeting to talk with me behind a closed door. “Am I glad to see you!” he said, and he told me he had been asked by the Bank of Greece to establish a new economics research center in Athens. He had a leave of absence from Berkeley and a Fulbright to cover his own costs, but he needed support for research projects, visiting professors, graduate students and the library. Would the Ford Foundation help?

On my return to New York I reported the conversation to Shep Stone, and Shep said, “Bring him in.” At a subsequent lunch in the Foundation’s dining room, Shep encouraged a written proposal. This led the following year to a general support grant of about $150,000 to the Athens Economic Research Center, now a Bank of Greece affiliate.

1964: I was assigned to the Karachi office of the Foundation as assistant representative. Andy’s father, Georgios Papandreou, had become the Prime Minister of Greece. Andy had renounced his American citizenship and left the research center to become minister of state in his father’s cabinet, in effect the assistant prime minister.

En route to Pakistan, my family and I were planning a two-week vacation in Greece. On our arrival at the hotel we were informed that the minister’s car would pick us up at a given time.

The limousine delivered us to Andy’s palatial beach house at Piraeus, a fashionable resort outside Athens. In the driveway, Andy introduced us to his departing guest, Aristotle Onassis, who took our place in the limousine. The Hertzes were then divided into three different rooms—my wife Stevie with Andy’s American wife, Margaret; Alan, age 10, and Miriam, age 6, with Andy’s son George, age 11; and I with Andy. We were all reunited for dinner at 10 p.m., the Greek dinner hour.

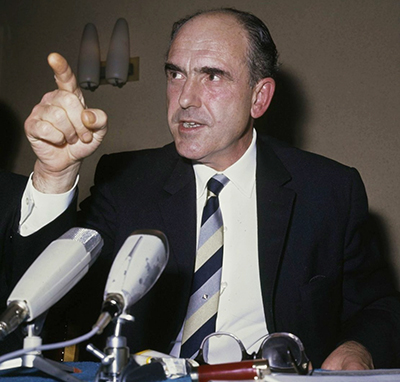

My session with Andy was memorable. Berkeley was furious with Andy for going into the messy world of Greek politics rather than returning to California, and he was worried about burning his bridges with the Foundation. In a one-hour emotional harangue, parading around the room with Scotch glass in hand, he defended his decision as a response to the call of duty to his country after years of corruption and mismanagement. I could not get a word in edgewise.

I reported the conversation to Shep in a written memo. In his answer, Shep, never non-plussed, took it all philosophically. In working in Europe, particularly in Greece and the Balkans, he wrote, you have to expect politics to exert a strong appeal to sheltered under-paid academics. “It goes with the territory,” he said.

As things turned out, the Papandreous took a neutral stand in the Cold War and criticized the massive presence of American military and intelligence in Greece. In 1967, father and son were overthrown by a junta of Greek generals, backed, Andy claimed, by the CIA. Georgios was put under house arrest, and Andy, after an eight-month imprisonment and the appeal of several American economists, was freed to go into exile.

1973: I was appointed assistant secretary of the Foundation, and Andy had settled in Canada and was working as a professor of economics at York University.

In 1974, after the generals themselves were ousted, Andy returned to Greece as head of a new political party, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK). In 1981’s general election, PASOK won a landslide victory and Andy became Prime Minister. In 1985 he was elected for one more three-year term, along the way divorcing Margaret and marrying an Olympic Airways hostess.

In 1989 things took a downturn. Andy was indicted by Parliament in connection with a $200 million Bank of Crete embezzlement scandal, temporarily ending his political career. In 1992, however, he was cleared of all wrongdoing, and he bounced back by being elected to his third four-year term as Prime Minister.

In January 1996, halfway into his third term, Andy resigned after two months in the hospital for lung and kidney failure, and he died in June.

Young George Papandreou—the youngster at the beach house—grew up to become the third member of the Papandreou family to be Prime Minister. Elected in 2009, he was forced to resign in 2011 because of the Greek government debt crisis. He is now the president of the Socialist International, a worldwide association of political parties.

Years later I visited Shep at his Vermont farm, and we reminisced over drinks about the sequence of events involving three generations of Papandreous. He did not know about my initial relations with Andy at Harvard, and he commented on “the perils of unintended consequences” for both of us.

|