NEWSLETTER

|

A Look Back at Funding Liberation Struggles By David Bonbright

David Bonbright, who worked in the Foundation’s Africa and Middle East program from 1983 to 1987, a crucial period in South Africa’s modern history and its involvement with the Foundation, continues the story begun in the previous issue and examines the possibilities for “new areas for inquiry and discussion.”

“What worked?” he asks. “What didn’t? Why? What are the lessons for social justice grantmaking today?” His “ruminations” on these and other questions “offer a couple of working hypotheses that currently preoccupy me.”

The Foundation’s programming in South Africa grew five-fold in what turned out to be apartheid’s last decade, and had three inter-related and overlapping themes.

The first was human rights and fairness. We supported efforts to use the limited legal and regulatory space available within the apartheid system to express and defend human rights and fairness principles.

I cannot quote him exactly, but I remember clearly the argument that Archbishop Desmond Tutu made to us. He fully expected to lose every case we brought to the courts. But he felt that it was important to make the case that justice and law are not the same thing, and that an unjust legal system can and must be challenged. Otherwise people may come to see law itself as illegitimate.

We funded direct legal services—ranging from community-based rights advice offices to public-interest law litigation—and research. Both the direct service and research work attracted the ire of the apartheid state, with our grantees often attracting official persecution. The only progressive legal work that we did not fund was the defense of the politically accused as this had adequate funding from the international anti-apartheid movement and, in any case, would have been challenged as being so directly political as to be against United States law.

I have long suspected it was our support for human rights research—and in particular support for the first scholarly book published on torture in South Africa—that resulted in my being declared persona non grata in 1987.

Our lawyer grantees played an important role here as well, defending the right of citizen groups to associate despite state persecution. South Africans, black and white, are churchgoers, and we supported the high-profile organizations that associated themselves with the liberation struggle, like the South African Council of Churches, headed by then Bishop Tutu, and the Southern African Catholic Bishops Congress.

An important sub-theme was expression and voice. We tended not to fund the international anti-apartheid campaigns because we believed our scarce resources were best invested in local voices. We supported the first black-led publishing house, Skotaville Press, and a range of documentaries, plays and books that fed a steady stream of home-grown stories to the global anti-apartheid canon.

But the main thrust of these grants was to fund intermediary organizations of trained professionals who were directly supporting the broader liberation movement. Many provided legal representation for the black trade unions and the pre-eminent national political organization, the United Democratic Front, including the activist lawyers at the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS).

Many of these professional NGOs, including CALS, were predominantly white, with roots in the more progressive universities and churches. They spanned every field of endeavor, from the environment and pre-schools to primary health care, rural development and distance education. They shared a clear purpose: to end apartheid and establish democratic equality in social, economic and political spheres.

The third theme was black leadership. Sometimes we spoke of this work in instrumental terms: the future will require black South Africans to run government and business. Sometimes in normative terms: democracy in South Africa is intrinsically about black leadership. We took our cues from the few areas where black leadership was already evident: the churches, the trade unions and NGOs aligned with the black consciousness movement. The goal was to transform organizations and communicate a clear message: white leaders had to move over and encourage black leadership to emerge.

To the historically white universities, we offered seed funding for programs to advance black graduate students and black faculty. At least one prominent university chose not to take up these grants on the grounds of a common white liberal view against “positive discrimination”. One of the beacon institutions of liberal ideology, the South African Institute of Race Relations, lost its longstanding support from the Foundation when it missed the opportunity in the early 1980s to hire a black person for even one of two leadership recruitments.

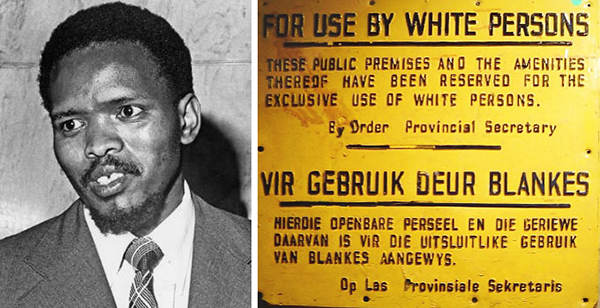

One of the important sub-themes was the extent to which our grantees were consciously modeling a post-apartheid society. The black consciousness (BC) movement of the 1970s led by Steve Biko unsettled and disrupted the world of old and young activists, white and black, with its critiques of white liberal politics and the “non-racial” tradition of the Congress movement. It contributed importantly to the 1980s mass democratic movement that, despite adopting the symbols of the Congress tradition, was in reality a very new phenomenon.

BEACHCOMBING FOR LESSONS

So what can we glean from this work 30 years later? This is a big question that merits more attention than I can give it here. But here are a few propositions that stand out much in the way a beachcomber comes upon collectibles on a long morning’s walk.

With respect to our human rights and legal services work, lawyers and judges funded by the Ford Foundation were prominent, if not dominant, in writing and defending the new democratic Constitution. They also played an important role in much of the redistributive and restorative justice work in the 20 years since South Africa became a democracy, ranging from land to housing to education to health services.

We cannot know whether the efforts of these individuals, or others like them, would have led to similar results in the absence of Ford Foundation support. But there are few who would argue against the proposition that the judiciary has been and is today the most effective public institution of the new South Africa. The courts, and particularly the Constitutional Court, have repeatedly led the ANC government back to Constitutional principles and away from the corrupting effects of power. It is fair to say that the judiciary remains the bedrock and bulwark of South African democracy today, just as we hoped it would be when, controversially, we started sending sitting apartheid judges (who were all white) to attend the Aspen Institute’s international human rights seminars.

The interregnum between the unbanning of the ANC in 1990 and the April 1994 election of Nelson Mandela was a fertile time in which a number of enduring building blocks of a democratic civil society were laid, including: nine provincial NGO associations uniting in a national federation (SANGOCO), the first national association of grantmakers (SAGA), a nonprofit internet service provider that introduced email and online data sharing (SANGONeT) and a national participatory consultative process that led to one of the early laws passed after the first democratic election, commonly known as the NGO Bill.

All of this grew directly from Ford’s work in the 1980s, something I can attest to first-hand since I instigated much of it from my post-Ford persona as the founder of the country’s first NGO dedicated to promoting civil society per se, the Development Resources Centre.

Over the two decades since the 1994 elections, South African civil society has had its ups and downs, but it remains vibrant, diverse, creative and open. It is largely funded with local resources, including steady government funding in politically safe areas like social welfare. The Mandela government drew heavily on civil society for its leadership, and it remains a training ground for government service.

But, looking back, we can see that civil society, including the government-affiliated trade union movement, was not just eclipsed but it was emasculated by the new democratic state. It certainly was not able to convince government to invest in the kinds of participatory and accountable governance that were the hallmarks of the liberation struggle.

The former head of the largest trade union confederation, COSATU, and the Minister for Reconstruction and Development in the Mandela Government, Jay Naidoo, has argued in recent years that the greatest mistake of government after coming to power was the demobilization of civil society in the attempt to create a “development state”. Only now, as grassroots protest against incompetent, corrupt and unaccountable public services swells to a level that suggests electoral vulnerability, is the ANC beginning to look at working with civil society to cultivate citizen voice.

Black leadership today is a given. Our work in the 1980s to promote black leadership seems anachronistic now. Leadership today is not about who, but about how. How to root out growing corruption? How to help create and support the citizen challenges that will force the ANC to rediscover and renew its internal democratic principles? How to build an effective political opposition to the ANC? How to transform the organizations of government and business—both brimming with talented, idealistic people—so that they remain responsive and accountable to citizens? How to match the material aspirations of the “born frees”, now entering the workforce, to the task of renewing South Africa’s democratic ideals?

On the other hand, the need to examine the psychosocial conditions of racism remains painfully relevant. How might the challenges of corruption and weak governance generally relate to unexamined issues of identity?

A CASE OF SOUTH AFRICAN EXCEPTIONALISM?

Looking back, I see three distinct conditions prevailing in South Africa in the 1980s that propelled our grantees forward.

First, however repressive the apartheid system was, the society was open enough for a democratic alternative to be expressed and to gradually win over the status quo ante.

Second, civil society and, in particular, the professional intermediary NGOs (our natural grantee community) were broadly and meaningfully accountable to authentic black leadership. Third, the century-long struggle of black South Africans for political rights had formed a genuinely democratic culture of inclusive consultation and attention to the psychological dimensions of liberation.

The domestic wing of the political liberation movement was essentially democratic in character. Inside the country, inclusive democratic practices were extolled and assiduously practiced, perhaps most famously within the trade unions. The two main exiled political movements, the ANC and PAC, were engaged, however, in armed struggles against a murderous opponent, causing them to develop a distinct sub-culture of military command-hierarchy that was only partially subordinate to civilian leadership.

Looking back, I see that I did not fully appreciate the distinctiveness of these three conditions at the time. But over time I have come to see them as pre-conditions for effective social justice work, and I have tried to establish them as part of everything that I do. Let me try to explain how.

As ruthless as it was, apartheid South Africa in its susceptibility to moral, political and economic pressure was more like the British Raj that Gandhi fought in India than Assad’s Syria or even Putin’s Russia. The international cultural and sport boycott was a hammer blow to white South Africa’s conviction that it was part of western civilization. There was enough opportunity in cultural, legal, social and economic domains inside the country to champion justice and demonstrate democratic principles.

I tried to avoid getting into arguments with ordinary apartheid supporters, but sometimes they could not be avoided. One I will never forget was on a flight from Rio to Cape Town. The flight was almost empty, with only about 25 white South Africans heading home after a holiday. They somehow drew me into a debate in which it quickly became clear that I was better informed than they were about the political protests then in the headlines. Once this became clear, their arguments retreated to the colonial cliché: “We know our natives.”

The debate, which had become quite heated, ended abruptly when I asked if anyone had ever been to an African’s home for a social event, whether they actually had any relationships with Africans that were not, in essence, those of master-servant. By 1985, this planeload of affluent white South Africans understood enough to be shamed into silence by the answers to those questions. They were ready to recognize that the rest of the world had left them behind, and that they had to change if they wanted to return to the community of civilized nations. But they were afraid and they did not see a way to do it.

By 1989 many white South Africans had come to understand something further, something almost miraculous. Namely, that they were in a lifeboat together with all South Africans and that their prospects were inextricably bound together. They finally understood what aboriginal Australian Lila Watson meant when she told the social worker, “If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

A decade of black trade unionism and the diverse activities of the United Democratic Front had enabled diverse whites to mix with politically unyielding blacks and build relationships with them, even if often across the table.

During these years it was far from clear that South Africa was moving in the right direction. Nor have I come across this level of societal understanding again in the two decades since living through “the South African miracle”. But I have seen its absence undermine development processes again and again.

My work today cultivates this sense of how relationships matter in social-change processes through a methodology of organizational performance management known as Constituent Voice, which enables organizations to listen and respond to the people they intend to help. I know that performance management systems can be bloodless, but they don’t have to be.

In our work in the humanitarian response to the 2014-2015 Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone, for example, we conducted weekly and bi-weekly short surveys of frontline health workers and citizens. The resulting first-of-its-kind data set clearly showed how and where the absence of trust between the humanitarian response and citizens was fueling the epidemic. The data also showed that frontline health workers were well aware of the trust gap and that it should be more carefully heeded by those higher up the hierarchy. Our Ground Truth surveys led to a series of rapid course corrections by Ebola prevention responders, particularly with regard to quarantine protocols.

Slowly, we are winning the argument in the humanitarian community that since relationships drive results it is necessary for all humanitarian interventions to lead with light-touch ask-and-respond mechanisms that test assumptions, discover hidden issues and engender trust and cooperation.

Constituent Voice is just one tool to realize the required quality of relationships that we want in development and social change. Among other suggestions, I agree with Robert Chambers’ prescription that funders have regular periods of immersion in the communities affected by their funding.

I came to a new appreciation of the second precondition present in South Africa of the 1980s—NGO accountability—when, in the late 1990s, as a new generation of philanthropists and governmental international aid donors started to push for their version of accountability. The new donors were preoccupied with seeing concrete measures of the results from their grants, so their push for accountability was really about more evaluation. This promoted a two decade-long search in development circles to find metrics that actually lead to improved outcomes or, in other words, metrics that actually do what they are supposed to do.

My main take-away from these decades of the quest for measurement in social change is that where you sit depends on where you stand. Different constituents in the ecosystem see the same things in different ways. When it comes to complex emergent problems—the kinds of problems that normally fall under the headings of social justice and sustainable development—there are no one-size-fits-all metrics. What meaningful data we can gather needs to be filtered through a collective learning process in order to arrive at the shared understandings of reality that make the best reference points for organizational decision-making. This insight is at the heart of the theory of measurement that lies behind Constituent Voice methodology.

The lesson from South Africa in the 1980s for today’s metrics mavens is that you don’t need to impose measurement on a system in which the organizations are in fact accountable to those who are meant to be experiencing the benefits of those organizations. When their voices matter, those primary constituents will find the best way forward and they will do so on their terms. This is the source of one of our taglines for Constituent Voice: “customer satisfaction for social change”. As Dennis Whittle says, “When the people are sovereign, the experts will be most effective.”

The third precondition can be summarized as the impossible-to-overestimate importance of means in determining ends when it comes to social justice and sustainable development. If you want to empower people, you work with them in a way that honors their agency. This is the mantra of participatory development, and there is nothing terribly original in it some 70 years after its emergence in the action-research paradigm out of Word War II.

But why is it so often neglected? Why is it that in 2015 only the smallest fraction of social change work is informed by rigorous practices of collective learning? I hypothesize that the answer lies in the failure to use systematic metrics to manage the quality of participatory practices. As evidence in support of this I have studied the rigorous constituent-centered measurement and learning practices of consumer-facing businesses. Businesses use customer satisfaction methods like Net Promoter Score to manage to a consistency of service delivery across large organizations. Imagine if citizens and implementers and funders could reliably and easily inform their actions regarding a particular development activity with rigorous feedback from those who had experienced it.

AND SOUTH AFRICA TODAY: STILL EXCEPTIONAL?

Looking back 30 years, how do we judge the fabled democratic principles of the South Africa liberation struggle? The idealism of solidarity and social justice that was central to the struggle seems to have given way in the new South Africa quickly to self-enrichment and self-dealing.

What is the legacy of the democratic liberation struggle for the practice of South African democracy in 2015? Perhaps it is enough that South Africa remains open enough as a society to enable us to hurry through an inevitable and necessary societal learning process and come to grips with the fundamentally creative process of innovating the organizations, systems, practices and tools that will let the people be sovereign.

Amartya Sen identified two essential conditions of development. One is individual human agency, and the other is the institutional arrangements that enable human agents to achieve just societal outcomes. South Africans have not finished drawing from the deep well of the legacy that is the democratic resistance struggle.

The example of Mandela may yet prove to be determinative, just as we can hope the noble narratives of the 18th century revolutionary founders may inspire reform closer to home.

A sidebar from Alliance Magazine:

THE SOROS CONNECTION

From early 1984, at the request of Frank Thomas, president of the Ford Foundation, I had been acting as an informal South Africa program officer for George Soros, who at that time did not have his own staff dedicated to working on South Africa. In late 1986 and early 1987 Soros decided that South Africa was heading for civil war and he very publicly said so, announcing that he would no longer be funding there. I remember trying to convince him to hang in there, but I also remember not being sure that he was wrong.

After Mandela was released and South Africa began moving purposefully, if vertiginously, towards democracy, Soros made another about face. He held another press conference and announced that he had been wrong, and that he was endowing a new local fund to promote open society in South Africa.

Soros was the first international grantmaker to endow a local social justice organization in South Africa. In correcting his error, he also set an important new benchmark for international philanthropy.

The Ford Foundation in South Africa: Part 2 The Ford Foundation in South Africa Part 2: Intro A Look Back at Funding Liberation Struggles by David Bonbright The “Drivers” Behind Ford’s Critical Work in the 1980s by David Bonbright Lessons from South Africa For Enhancing Philanthropy by John Gerhart

Links to Part 1:

The Ford Foundation in South Africa: Part 1

Pioneering Human Rights by Sheila Avrin McLean

Visions of Johanna: Inside the museums, apartheid goes on trial by Gerry Salole

Letter: The Ford Foundation in South Africa by Willard Hertz

|