NEWSLETTER

|

Lessons from South Africa For Enhancing Philanthropy

This article by the late John Gerhart first appeared in the March 2004 issue of Alliance Magazine and is reprinted here with minimal editing.

It is, in essence, a speech he gave four years earlier at a Conference on Indigenous Philanthropy held in Islamabad, Pakistan. He was president of the American University in Cairo at the time and drew on his experiences with the Ford Foundation in several offices in Africa over the previous decades, especially in South Africa, to suggest a path to “a healthy private philanthropic sector in every country”.

While many of the circumstances and statistics cited here have changed over time, the lessons learned remain valid.

By John Gerhart

The South African experience may have useful parallels with the situation in Pakistan. Both countries possess vibrant private sectors, a rich array of community-based organizations, and a strong tradition of religiously motivated giving to social causes. All three characteristics are important for the development of a healthy philanthropic sector.

THE CASE FOR INDIGENOUS PHILANTHROPY

The case for a healthy private philanthropic sector in every country is overwhelming. Governments are constantly hard-pressed to meet basic needs and to perform basic functions and will never have the resources to fully meet the needs of the disadvantaged in society. Moreover, local knowledge of problems and of resources is essential to the effective design, execution and evaluation of successful programs…. International donors usually have an uneven geographical distribution of effort and short, emergency-oriented approaches. Moreover, even where international donors are active, they seldom have the local knowledge, language, commitment or resources to make a lasting impact. Only a long-term sustained effort to address the causes as well as the consequences of poverty is likely to succeed.

THE INFRASTRUCTURE FOR EFFECTIVE INDIGENOUS PHILANTHROPY

….There has been a rapid growth in indigenous organized philanthropy in developing countries in the past decade and some generalizations can be made about what enhances effective development of indigenous philanthropy. Country studies…indicate that between 6 and 10 per cent of Gross Domestic Product may be attributed to the non-profit sector, which employs tens of thousands of people. National accounts in many countries are being modified to measure this “third sector”. Tax policies have been recognized as an important stimulus to philanthropic giving, although personal motivation, especially religious motivation, lies at the root of all philanthropy. In some countries, including Mexico, Brazil, South Africa and the Philippines, organizations of private foundations and donor agencies have played an important role in promoting beneficial public policies and improved giving among private donors.

….Geographically based community foundations are one example of a rapidly growing specialized form of philanthropy, and community foundation networks exist in North America, the United Kingdom, South Africa and Africa more generally. South Africa offers one example of how quickly a philanthropic infrastructure can develop, and the types of institutions that have grown along with it.

Prior to 1989, the independent or non-governmental sector in South Africa had experienced half a century of vigorous growth in spite of constant harassment from a government bent on racial separation and domination. Successive National Party governments neither recognized nor sought to provide for the basic social needs of the majority of the population, and South Africans of color, whether of African, Asian or mixed race origins, by and large sought to avoid government control. Foreign governments, voluntary organizations and donors also refused to deal directly with the South African government, but provided considerable support to South African NGOs, mosques and churches directly.

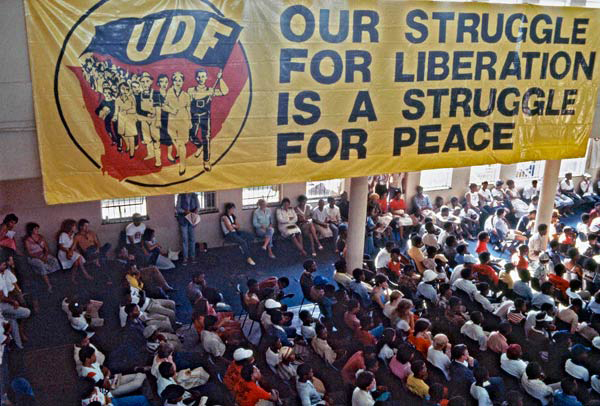

Precisely because of government attempts to control NGOs in general and foreign funding in particular, there was little transparency in the sector, rather limited sharing of experience, and few, if any, national organizations representing the non-governmental sector. The most important ones, the South African Council of Churches and the United Democratic Front, were accused by the government of being agents for the outlawed opposition political movements. Their leaders were frequently arrested and their offices were bombed. Moreover, because of the state of emergency that prevailed, external donors were reluctant to criticize NGO leaders or enforce strict reporting requirements on independent organizations.

All this changed abruptly after 1989, when it became clear that the National Party government was prepared to reach a negotiated transition to democracy in South Africa. Constraints on external funding and internal organizing were effectively dropped. While the move towards democratic government drew many NGO leaders into government ranks, the stage was opened for a flourishing of new organizations within the independent sector. Over the next few years a number of key local, regional and national organizations developed, modelled in many cases on similar long-standing institutions in the U.S.

International donor agencies were able to support these organizations freely, both with funding and ideas. (Four of the key organizations were assisted in their establishment by the Development Resources Centre, an independent NGO founded and headed at that time by David Bonbright…. )

INFRASTRUCTURE ORGANIZATIONS FOR THE INDEPENDENT SECTOR

A number of national infrastructure organizations grew up in South Africa, serving the voluntary sector in general and the philanthropic sector in particular. These included:

The “Independent Study” Early on it became clear that the relationship between the state and the independent sector needed some formal definition. The South African state had established very narrow and controlling registration and taxation policies that were neither necessary nor sufficient for a healthy growth of the independent sector. An Independent Study into the Enabling Environment for NGOs was established by the Development Resources Centre, drawing on a very wide range of independent organizations and steered by a committee of eminent civic, religious and business leaders.

More than 2,000 NGOs participated in the meetings of this commission, spread over two years. While almost every aspect of the commission’s report and mandate were challenged by some element of the independent sector, nevertheless the commission’s report resulted eventually in a progressive reform of government registration policies. But perhaps its greatest contribution was to create a context in which NGOs, business and public officials (in waiting) could deepen their understanding of each other and come to see the pivotal role of the legal and fiscal framework.

South African NGO Coalition An early and intended outgrowth of the Independent Study process was a national organization of NGOs, known by its acronym SANGOCO. SANGOCO has about 4,000 member organizations, organized with nine provincial councils (some with several hundred member organizations) and some 19 functional or thematic councils (women, land, small enterprise, conservation, children, health, adult education, etc). With this kind of open membership, SANGOCO has a breadth that makes it a legitimate voice for NGOs in speaking to the government, the public and the donor communities. SANGOCO also organizes and negotiates low-cost travel, insurance, training, car rental and other services for member organizations. SANGOCO commissioned a study of tax policies relating to the independent sector that advocated more liberal tax treatment of donations along the lines made famous in the U.S.

Southern African Grantmakers’ Association This organization of donors has some 86 member organizations, including corporate grantmakers, private foundations and a few international donors who are represented in South Africa. SAGA, as it is known, promotes “best practice” among donors, shares information, has national seminars and training programs, and represents the donor community in dealings with the government and the public. It advocates transparency among donors, including the publication of annual reports and easy-to-use procedures for grant applicants…. It has been sustained by membership contributions and grant funding from the US-based Ford, Kellogg and Mott Foundations and the Liberty Life Foundation of South Africa. It has lobbied for better tax treatment for non-profits of all kinds.

South African NGO Network SANGONeT, as it is known, is an electronic network that provides low-cost services, including training, to South African labor and non-governmental organizations. It has about 1,000 subscribers, about 20 per cent of whom are individuals. It began as a project of the Development Resources Centre and is now an independent organization. While it was originally grant funded, it is now largely self-sustaining.

Prodder Prodder is also an electronic news service that regularly publishes a list of meetings, conferences, seminars, training programs, publications and resources for the independent sector. It typically makes a free weekly electronic mailing to all subscribers. It reports on major events and occasionally has editorial pieces about important issues.

Non-Profit Partnership This interesting organization was set up jointly by SANGOCO, SAGA and the UK-based Charities Aid Foundation to promote voluntary and corporate giving and the reform of tax structures to broaden the definition of organizations eligible to receive tax-deductible gifts. It also provides financial services and investment advice to NGOs.

Impumelelo Innovations Award Program Among the many interesting organizations that have developed in South Africa since the advent of democratic elections is this project to recognize innovative partnerships between government and the independent sector in the delivery of social services. Annual awards are made each year on the basis of a carefully conducted competition.

Community Foundation Project The Southern Africa Grantmakers’ Association sponsors a service to assist the establishment of endowed community foundations in South Africa, again modeled on British and American experience, but driven by partnerships with local business leaders….

Regional technical assistance organizations In addition to the rich range of infrastructure organizations listed above, South Africa has a number of well-established regional technical assistance and training agencies that operate as NGOs serving smaller community-based organizations. Olive (in Durban), the Community Development Resources Agency (in Cape Town) and the Development Resources Centre and Sedibeng (in Johannesburg) are all examples of such organizations. In addition, a justly famous network of human rights organizations (the Legal Resources Centre, the Black Sash and others) provide legal advice to institutions in the independent sector.

Research organizations While there is as yet no established national research program dealing with the independent sector, several organizations undertake studies and monitoring of the sector. Most notable among these are the School of Public and Development Management of the University of the Witwatersrand, the Institute for Democracy in South Africa and the Centre for Policy Studies, an independent research center….

The above brief outline indicates the rich organizational structure that has developed to serve the independent sector in one country, South Africa, all in less than ten years. None of the above organizations were developed by government and none were the creation of foreign bilateral donors. This largely indigenous development was fortunate because it coincided with a substantial shift in international funding away from the independent sector towards the newly elected government, and in some cases away from South Africa itself. In particular, the European Community, which had been by far the largest donor (probably accounting for more than half of all funding to voluntary organizations), terminated its program abruptly after 1994. Many other European governments and churches also reduced their aid programs in order to address pressing problems in South Eastern Europe and other places. USAID, to its credit, sustained most of its independent sector funding. On balance, however, South Africa demonstrates clearly the dangers to the independent sector of an over-reliance on foreign funders.

How, can the independent sector establish a more robust and sustainable funding base?

Maximize the diversity of funding sources Organizations should seek funding from the widest possible range of sources: government, bilateral donors, corporations, patrons, membership organizations, professional associations, etc. For sustainability, the number of supporters may be more important than the amounts. Many donors also provide more sources of contacts and information.

Seek to build up self-generated funds Developing fee-for-service schemes, property rental, consulting services, paid training programs and the like can build a substantial base for independent organizations.

Build individual giving programs Although the amounts of membership fees and annual fund donations may be initially small, they may lead to much more valuable contributions of ideas, voluntary time, connections to other donors and eventually bequests.

Build corporate relations and giving Organizations should be much more proactive in seeking corporate sponsorship. Some types of activities (sports, health programs, arts festivals, etc) lend themselves nicely to corporate sponsorship and offer multiple opportunities for publicity for the donors. Voluntary, pro bono activities by corporate employees often lead to substantial funding as well.

Improve taxation policies Non-profit organizations need to lobby for tax exemption for certain activities and for greater eligibility for tax-deductible contributions. Corporations, individuals and estates should all be given established deductions (usually 7 to l0 per cent of pre-tax profits for corporations and up to 50 per cent for estates) for gifts to qualifying non-profit organizations and universities. Experience in the U.S. indicates that tax-deductible donations have a substantial multiplier effect: the amounts given are at least four times the losses in tax revenue resulting from the donations.

Endowments Even small organizations should seek to build administrative and program endowments or reserve funds, adding to them earned interest, unexpended funds or one-time gifts as the donors permit. International donors are much more likely to give to organizations that have demonstrated a long-term commitment by establishing endowments for administrative costs. Tax exemption for bequests to qualified non-profit organizations is extremely important to the formation of endowments.

Community foundations The fastest growing sector of philanthropy in the U.S. is area-based community foundations, which pool gifts from many sources and share high quality professional staff and volunteers. Community foundations have also proved valuable intermediaries in solving communal disputes and they act as key planning agencies in most American cities. A community foundation movement has also succeeded in the U.K. and is under development in other countries.

Contracting with state agencies Non-profits are far more effective than bureaucracies in delivering certain types of services to the community. Day-care, eldercare, school feeding, vocational training, counseling and many other services can be provided more cheaply and sensitively through contracts between independent sector organizations and central, regional and local governments. Though these relations take time to develop and to monitor, they are well worth the effort and can provide a significant income for many non-profits.

Direct government funding Ironically, direct government funding is one of the least successful forms of support for non-profit organizations (as opposed to competitive contracting for the provision of services) and works well only in fields such as the arts, where there are arms-length competitions. Government funding is subject to political pressures and often brings with it bureaucratic requirements that are hardly worth the effort.

Information sharing One of the most cost-effective means for improving local philanthropy is sharing experience among private donors. Many donors have the means and the motivation to give but are reluctant to publicize their wealth or to take chances on having their funds misused. An environment of sharing of ideas among donors is often conducive to building confidence and increasing the reliability of grantmaking. A local center for philanthropy can provide the core institution for information sharing and can encourage the formation of both family and corporate foundations.

Sharing training and services Like anything else, grantmaking can be done well or badly. A grantmakers’ association can help its members by promoting “best practice” and professionalism among donors, by pooling donor resources and by training donors, their board members and their employees. Moreover, the costs of feasibility studies, public education campaigns and the like can be shared among like-minded donors.

Representing the disadvantaged When donors act or speak collectively, they can exercise enormous power for good in a given society. An association of grantmakers, therefore, may be more effective in representing the needs of the poor than the poor are themselves. This is an important social responsibility for grantmakers that should not be ignored.

Setting ethical standards By acting together, grantmakers can encourage the establishment of best practices and ethical standards among themselves and among recipient organizations. This can be done both by practice and by giving awards and recognition to innovative projects. Providing regular information about grant requirements and procedures can enhance the effectiveness of grantseekers, thereby saving time and promoting better project formulation.

These few recommendations can lead to enhanced indigenous philanthropy and, for they go together, to the creation of a healthier, more self-confident and more self-reliant independent sector.

John Gerhart was a graduate student at Princeton University in 1968 when he was recruited to be a summer intern in the Nairobi, Kenya, office of the Ford Foundation. He was hired as a program officer there the next year and worked for the Foundation for the next 29 years. He was a Ford-sponsored technical assistant in Botswana’s Ministry of Agriculture, assistant representative in the Nairobi office, representative in Cairo from 1980 to 1985, a deputy vice president in New York from 1985 to 1992, and then representative in Johannesburg, opening the Foundation’s first office in South Africa in 1993. He left Ford in 1998 to become president of The American University in Cairo.

The Ford Foundation in South Africa: Part 2

The Ford Foundation in South Africa Part 2: Intro A Look Back at Funding Liberation Struggles by David Bonbright The “Drivers” Behind Ford’s Critical Work in the 1980s by David Bonbright Lessons from South Africa For Enhancing Philanthropy by John Gerhart

Links to Part 1:

The Ford Foundation in South Africa: Part 1

Pioneering Human Rights by Sheila Avrin McLean

Visions of Johanna: Inside the museums, apartheid goes on trial by Gerry Salole

Letter: The Ford Foundation in South Africa by Willard Hertz

|