NEWSLETTER

|

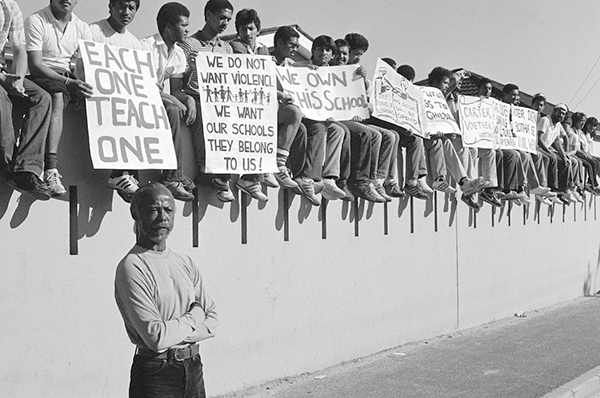

Developing Black Leadership Fellowships are provided for emerging social scientists By David Smock

As an initial toe in the water we funded two unexciting projects. One was the South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR), where Foundation funds paid for much of its research program. SAIRR was a liberal white organization that documented the state of race relations in South Africa.

The other project was the United States-South Africa Leader Exchange Program (USSALEP), which funded trips to the U.S. by leading white South Africans and trips by American leaders to South Africa. The underlying purpose was to influence white South African leaders to be more liberal and more critical of apartheid. It had some positive influence on the margins, but there also were instances in which the conservative South African participants influenced white Americans to be more sympathetic to South Africa and its policies.

In 1974 I was back in the New York office as deputy head of the Middle East and Africa program and as adviser on the social sciences. Robert Edwards, who was the new head of MEA, and I decided we needed to be more creative in South Africa and engage with the black community. We thought we could fund social science research relating to apartheid undertaken by black scholars at South African universities, mostly black institutions. We decided to send an American social scientist to South Africa to map out a project.

We chose Richard Sklar from the University of California at Los Angeles, but he was unable to obtain a visa to South Africa because of critical comments he had made to the press about the country. Bob and I decided then that I should go and undertake the explorations.

I spent about three weeks visiting all the black universities and exploring what a social science research project might look like. I soon discovered that there were only a handful of black social scientists and none had the time to engage in research. Time and again I heard pleas that what was needed was a faculty development project for black staff at black universities.

So we abandoned the idea of a research project and developed a staff development project in the social sciences for black universities. We contracted with the Institute of International Education (IIE) to manage what was a relatively small effort, but it had a positive impact.

Then, in 1980, IIE decided it wanted to significantly expand the fellowship program for black South Africans. At the time I was Ford’s representative for East and Southern Africa, based in Nairobi, and IIE hired me to launch the expansion. We recruited Derek Bok, president of Harvard University, to lead the American council for the project and Archbishop Desmond Tutu to head the South African council. The American side of the project was called the South African Education Program and the South African side was called the Educational Opportunities Council.

Ford provided seed money to get the project started. On-going funding was provided by United States corporations, foundations, and colleges and universities. We sent students only to participating colleges and universities that provided scholarships. After the project was well established, expanded funding was provided by the U.S. government. Over a ten-year period the program provided scholarships to hundreds of black South Africans who earned degrees, both bachelors’ and masters’, at American institutions.

Virtually all those trained returned to South Africa to assume positions that were beginning to open up to blacks. They constituted a significant component of the emerging black leadership cadre.

The Ford Foundation in South Africa

Pioneering Human Rights by Sheila Avrin McLean

Visions of Johanna: Inside the museums, apartheid goes on trial by Gerry Salole

Letter: The Ford Foundation in South Africa by Willard Hertz

|