NEWSLETTER

|

Memoirs of an International Life

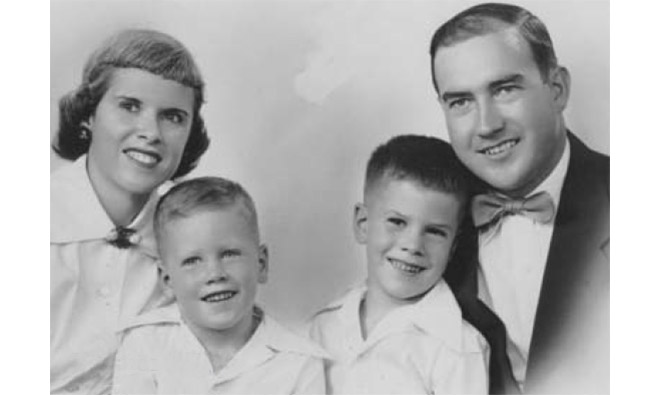

The following are excerpts from the self-published memoirs of William Gamble, who worked at the Ford Foundation from 1955 to 1975 across all international programs: Asia and the Pacific, Africa and the Middle East and Latin America and the Caribbean. He marked his one-hundredth birthday earlier this year, a celebration covered in the Winter 2020 issue of this newsletter.

His book is sub-titled “Remembering: Growing Up, Living and Working on Five Continents”, and in these excerpts he tells of when, in 1954, he was approached by the Foundation and offered a contract. He was working in Burma, now Myanmar, with the United States Department of Agriculture’s Technical Cooperation Administration (TCA), assigned to the country’s Education Division of Agricultural Education and stationed at the State Teacher Training College in Kambe, a suburb of Rangoon.

The memoir, as anticipated, is replete with personal and professional details, from mundane to physically harrowing, painting a full and fascinating picture of the life of a Foundation overseas representative and his family in the early days of Ford’s international work, including snapshots of some of the staff who helped develop the Foundation’s international program. The full book is available online (Click here for the “Memoirs of an International Life” PDF). The first excerpt begins “in early March 1954”.

About this time, The Ford Foundation established an office in Rangoon. Dr. John Everton and his family took up residence as the Representative of the Foundation. The Foundation was looking for interesting projects which would be in keeping with its policy to assist in projects that would advance human welfare. The Minister and Director of Education asked Dr. Everton to see if they would be interested in supporting the development of the Pyimana Agricultural Institute, since the U.S. TCA was being terminated.

John had hired Richard (Dick) Morse, who had been working in Education under the TCA program, to be his deputy, and Dick was quite familiar with the plans for the Institute. After consultation with the Foundation’s New York office, they advised the Minister that the Foundation would like to support the development of the Institute. The Minister and the Director of Education then strongly recommended that the Ford Foundation hire me to lead the development of the program.

John contacted me and we discussed the possibility of my joining the Foundation and continuing my work in Burma at the end of my 2-year contract, which was only about 6 months away. I was enthusiastic about the future of the Agricultural Institute but at that time knew nothing about the Ford Foundation. John laid out the proposal that the Foundation was prepared to provide major support for the overall program of the Institute as well as hire me to lead it. This was very encouraging since I knew that, while the Government would provide support for local costs, the cost of faculty from abroad (which was needed) and the foreign exchange cost for equipment and supplies would need to be covered by external funding,….

After considerable discussion with John, and with a strong request from the Minister and Director of Education, Virginia [his wife] and I decided we would accept a position with the Ford Foundation, if I could get a 2-year leave of absence from TCA. I put in my request for the leave of absence and was somewhat surprised to receive a cable from the then Secretary of State, Harold Stassen, approving the leave. In early June the details of my leave and a 2-year contract with the Ford Foundation to commence in January 1955 were completed….

I continued working almost full time on preparation for the opening of the college, which was given the Burmese name equivalent to the State Agricultural Institute. I had to draft a proposal for the 2-year academic program—subjects, number of semesters for each, a rough outline for each course—and identify the related fieldwork. I knew that the students coming in would [be] high school graduates from various ethnic groups, mostly from rural villages but with little or no real experience in agricultural and livestock production. We expected the graduates to leave Pyinmana prepared to directly work with and advise farmers or teach agricultural and livestock production in high schools, so they had to gain considerable practical experience.

With a great deal of consultation with my Burmese colleagues, it all began to come together….

In actually planning the class schedule, we had to consider the customary Burmese meal schedule. We decided on morning tea at 6 a.m., practical fieldwork from 6:30 until 8:30, breakfast at 9:30, classes from 10:30 until 3:30, dinner at 4 p.m. and then individual project activities or sports. We also decided that all 2nd year students would spend 3 weeks each semester in a village, living with families and working directly with the villagers on specific agricultural practices, with regular supervisory visits by Institute Staff….

He and his family moved into their house in early July, “the upper floor of a large brick bungalow”.

The house had not been occupied for 10 years, so repairs were required (which were underway). An outdoor toilet and servants’ quarters had to be constructed, and the well cleaned. We drew water from the well with a bucket until we got a hand pump rigged to pump water to the tank in the attic of the house. There was no electricity, so we had to find kerosene and gas pressure lamps and a kerosene refrigerator and stove (we used a kerosene refrigerator throughout our 5 years in Pyinmana).

It was just like going back to my parents’ early living conditions on the farm, and perhaps even a bit more primitive….

Later that month he traveled to New York City to officially become an employee of the Foundation.

My only contact with the Foundation up to that time was with John Everton, the Foundation representative, so I did not know what to expect. I was very pleased to receive a nice welcome at their offices on Madison Avenue, just behind St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The staff was very friendly and efficient in processing my paperwork, arranging for a physical examination, and briefing me on the Foundation’s operating procedures. It quickly became obvious that I was joining a talented group in an organization with a clearly defined goal of the advancement of human welfare.

I was given authority to recruit an agricultural engineering specialist for Pyinmana and after checking many references, I flew to Chicago and visited George Miller and family in Medaryville, Indiana. George and his wife had lived in Liberia for a few years when he worked for Firestone as a field engineer on their rubber plantation. I was very impressed with George’s qualifications and personality…so I offered George the position and he accepted. It proved to be a good choice….

After our return from the United States, I continued my teaching duties in farm crops and supervision of students’ fieldwork. I also started teaching chemistry and had to spend a great deal of time studying to keep ahead of the students….

It was soon evident that the students were not sufficiently advanced in English to participate in English in class. Most could express themselves in writing and understood English fairly well, but could not express themselves speaking it. At the same time, I could understand Burmese quite well but could not express myself as well in the language as was needed for teaching, so we worked out a system that met our needs. I lectured in English and led class discussions speaking English, while the students responded in Burmese. It was really very successful….

He visited India in October 1955 to observe agricultural colleges and village development projects funded by the Foundation. He learned much about the Foundation, agriculture in India—and Burma.

I appreciated how much better off Burma was than India. One difference that was particularly noticeable was the role of women. In Burma, when I visited a village or a home, the women were at ease and welcomed me, while in India when I visited a village, the women all retreated behind walls or covered their faces and would not talk to me. There were some women who worked on hand looms or as teachers in the villages impacted by Gandhi’s village development programs who were more open, but they were rare….

Soon after I returned from India, we had a visit from the Vice President of the Ford Foundation’s International Program, Dr. F.F. (Frosty) Hill, his wife Lillian and daughter Peggy, along with Dr. Everton of the Rangoon office. Frosty was educated as an agricultural economist and had an agricultural background in Canada, and Lillian was a plant geneticist. We very much enjoyed their visit. Frosty was born in Canada but had emigrated to the United States when he went to college. He had a distinguished career in the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration and had served as Provost of Cornell University. Ours was one of the first agricultural programs they had visited since joining the Foundation and Frosty became a strong supporter of the program and my work throughout his time as Vice President. This was the first time any of them had slept under mosquito nets and I remember they had lots of giggles while trying to get into their beds and get the nets tucked in.

I also accompanied them to Mandalay to visit the College of Agriculture…. We drove to Mandalay in a convoy with a truckload of soldiers in front, and a jeep full of soldiers following us as our security force….

There were still many insurgent troops in our area so the army was on regular alert and made frequent sweeps through surrounding villages, searching for insurgent leaders. When captured, the leaders were transported to Rangoon for trial. Often, for lack of evidence, they were soon released. The military, especially the Gurkhas, were upset about this and I remember the captain telling me that when they captured one insurgent leader for the third time they decided to not send him to Rangoon. Rather, they offered him the opportunity to try to escape, and told him if he made it over the hill they would never seek him again. Of course, he didn’t make it over the hill….

Visitors continued to swamp us every week. We had a number of visitors from the Foundation offices in Rangoon and New York—the Controller from New York and Vern Atwater, Director of Administration, New York. The Controller was a “dark suit, white shirt and tie” person. I finally got him to remove his suit jacket when I took him to visit our students in villages! Vern Atwater was a good guest and much interested in our living conditions. I arranged for him to visit the hospital where there was a patient dying of hydrophobia (from a bite by a rabid dog) and another patient who had been badly mauled by a tiger near his village. We observed many other patients in various states of emergency. Our doctor in Pyinmana always said if he had to operate on one of us he would do it on our dining room table since that would be much more sanitary than the hospital.

|