NEWSLETTER

|

Philanthropy in Africa and the “Enduring Network” of LAFF By Alan Fowler

The Ford Foundation creates enduring networks in mysterious ways. This reflection is prompted by the South Africa office’s funding for a “first” for Africa: a Chair in African Philanthropy at the Wits Business School in Johannesburg, which I will help establish as a visiting professor.

The Foundation earlier had funded the John Gerhart Center for Philanthropy, in Cairo, but not as an academic chair.

The story stretches back some 30 years to my stint as a program officer for public policy and governance in the Nairobi office. Of interest is what happened in the time between, a LAFF-like weaving of personal and professional relationships around the Foundation’s commitment to the co-evolution of a research infrastructure and philanthropy, or gifting, on the continent.

The recent planning grant to set up the Chair in African Philanthropy has many parents with Foundation links. A few milestones help trace the origins and trajectory through the people, moments and initiatives that contributed to this latest structural investment enabling the continent to study gifting in its own terms to better reflect, learn about and value itself.

A potential grantee in Zimbabwe working with Save the Children Fund, Gerry Salole, pointed out that among indigenous non-governmental organizations, “a quintessential African Institution was strangely completely invisible to development pundits and agencies who kept building bad copies of what people were already doing for themselves.”

Move on a few years to a model of “indigenously-connected” community foundations that was taking shape in the United States as well as being tested in other countries. In East Africa, initially hosted by the Aga Khan Foundation, Ford’s Nairobi program officer Tade Aina was stimulating formation of what has, for example, become the Kenya Community Development Foundation. The African Women’s Development Fund is a West

African example.

“In the book, The Charitable Impulse, published in 1989, I examined the relationship between wealth and social conscience in communities and cultures outside of the United States in order to demonstrate the universality of the charitable impulse.” (Foreword to The Poor Philanthropist, Vol. I)

His consistent search for learning about helping traditions of people with more limited wealth is a thread throughout much of what has transpired.

Ably led by Susan Wilkinson-Maposa, with myself as technical advisor, three Poor Philanthropist publications stemming from the initial CLPV research and follow-up studies shed new light on how and why people who are poor help each other. Results in terms of community foundation thinking and practice of “horizontalism” found resonance in the United States, as well as with other parts of the continent, shared, for example, through meetings of the Africa Grantmakers Network, another Foundation grantee. This “knowledge” grant meshed well with another major strand of the Foundation’s efforts for and on the continent.

All along, starting in the mid 1990s and together with others, the Foundation was supporting a nascent International Society for Third Research (ISTR). Complementing its “activist” local organization-building efforts, led by Michael Edwards, the Foundation was investing in the development of a global infrastructure to study what later became referred to as civil society. New York and the Foundation’s Africa offices were supporting ISTR global and regional conferences as well as a new Centre for Civil Society at the University of Kwazulu Natal with Adam Habib as its first director, serving with me on the ISTR board.

Fast forward to the Foundation’s Special Initiative for Africa (SIA). This effort was conceived in 2000 to counter the depressing international narrative of a continent without hope or capacity.

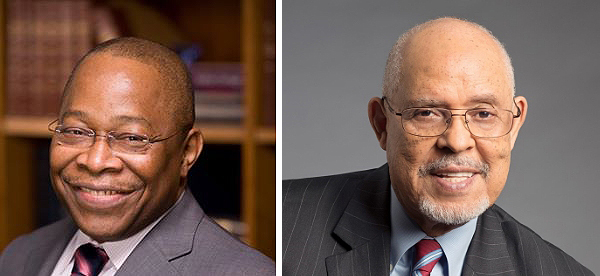

With Akwasi Aidoo and Bheki Moyo as its architects and first executive and program director respectively, in 2005 this incubating effort became embedded on the continent as Trust Africa, a further stage in infrastructure building.

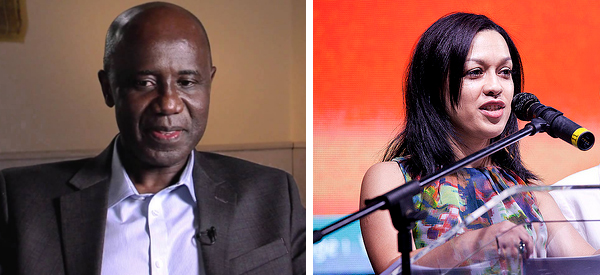

In our conversations, the Foundation’s current Representative in South Africa, Nicolette Naylor, describes this grant in the following way:

“We have all heard about the rise of new philanthropy in Africa where there is an increase in the number of self-identified philanthropists on the continent and people are talking and writing about this phenomenon but somehow no common agenda has emerged that brings together African narratives on philanthropy in a way that grapples with the ideological tensions between narratives from the West, drowning out narratives emanating from the continent.”

She goes on to explain that:

“In a context where the benevolence of Western private philanthropy is no longer assumed and instead heavily critiqued for undermining sovereign States on the continent it is critically important to unpack and critique notions of philanthropy that speak to the new geopolitical and economic moment that we find ourselves in. The Chair offers an opportunity to present alternatives emanating from notions of Ubuntu; religious teachings and communitarianism on the continent. The Chair may also offer a robust critique of philanthropic models imported from the United States by U.S. foundations. The Chair, in the spirit of Academic Chairs, is exciting because while it may make mainstream private foundations uncomfortable it will also allow for a deeper, reflective and thoughtful analysis, grounded in rigorous, innovative academic research and writing.”

The Chair is interesting at another level because it comes full circle in terms of the notion that networking paths can creatively lead back to Ford and to members of LAFF. Nicolette has been employed by the Foundation for nine years, starting her tenure in January 2007 as the Human Rights Program Officer based in Johannesburg. She was heavily influenced by the work the office was undertaking in partnership with other Africa offices to promote local philanthropy and its infrastructure. This was under the leadership of Alice Brown, the Representative in South Africa at that time, assisted by Halima Mohamed, who had worked alongside both Alice and, previously, Gerry Salole.

The combination of Alice Brown, Adhiambo Odaga, Tade Aina (Representatives in the West Africa and East Africa Offices) and people like Mike Edwards in New York, all influenced her thinking around philanthropy and civil society and its importance as a field of investigation for the continent.

During the early years as a Foundation Program Officer she was introduced to Trust Africa and heard of efforts by Tade Aina to catalyze the indigenous philanthropy in Kenya. Unfortunately, this was also at a time when the Foundation decided to dramatically reduce its funding toward a robust philanthropy program.

In her experience, the closure of the philanthropy portfolio in the Office for Southern Africa had a devastating impact on the exploratory investments of people like the late John Gerhart, Gerry Salole and Alice Brown. Their early work was geared toward strengthening local indigenous philanthropy and the civil society infrastructure for philanthropy to thrive, albeit from a U.S. perspective building on learning about U.S. models of philanthropy and community foundations.

As Nicolette was musing over how one could embark on studies in the field of philanthropy on the continent, Halima Mohamed had left Ford and completed her post-graduate studies in this field. They stayed in touch while Halima continued her path towards Trust Africa and, in this way, Nicolette became exposed to the work of Bheki Moyo and his exceptional thesis. Today Halima works as a consultant to Ford Southern Africa advising Nicolette on the philanthropy program in the office.

In June 2014, Darren Walker announced that Ford would reconsider its work on philanthropy and re-engage in the space. Nicolette was asked to join a Global Working Group within Ford to contribute to the debates that the institution was having as it restructured its work. The Working Group organized itself under the rubric “Philanthropy: Reboot, Reposition, Reimagine”.

Based on her institutional memory and recollections around earlier endeavors at Ford, Nicolette wanted to contribute to the discussions in a way that would build on the work of those who had come before her. Around this time, with great enthusiasm, she became engrossed with and inspired by the hefty volume Giving to Help, Helping to Give, edited by Tade Aina and Bheki Moyo.

Assuming the role of Representative in 2015, Nicolette started a series of dialogues with Bheki Moyo on the theme of African philanthropy. When, along with Adam Habib, Bheki Moyo presented the idea of a Chair in Philanthropy she did not take long to confirm her enthusiasm.

The office decided to cautiously re-engage in the space by supporting the Chair as a thoughtful, though as you will see from the quotations, thought-provoking re-engagement with knowledge generation and higher education. This step is happening at a time when the Foundation, led by Representatives on the continent, wants to embrace and support knowledge generation that emanates on the continent, for the continent and by leaders on the continent while fostering ties with Foundation offices in Asia that are similarly exploring these themes, and by learning from the rich experiences within the LAFF community.

An inaugural working seminar bringing together participants from across and beyond the continent will co-define the Chair’s pan-African character, agenda and profile. Once more, Foundation networking appears. In identifying participants for the inaugural seminar I came across LAFFer Mark Sidel, a fellow ex-president of ISTR, recently appointed visiting Chair in Community Philanthropy at the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University.

This personal story illustrates what seeds the Foundation sows and the relational webs it can create with LAFF as a collective holding space for them all. The serendipity of my history and new interim role makes the Chair in African Philanthropy a unique cooperation between LAFF and current leadership on the continent that should no longer be a question of chance.

Should, perhaps, the next 25 years of LAFF be characterized by a reinvigorated partnership with the Foundation by mutual design for mutual benefit? Where there’s a will there’s a way.

Alan Fowler is emeritus professor at the International Institute of Social Studies in The Hague, the Netherlands.

|

Comments (1) |

| Barbara Jane Klugman 4/25/2016 2:07:47 PM Hi Alan, this is all fascinating. Did you know that the Global Fund for Community Foundations (of which Gerry Salole is board chair) is based on Jo'burg - you may want to invite its director, Jenny Hodgson to your workshop - jenny@globalfundcf.org - Yours, Barbara Klugman (Johannesburg) |