NEWSLETTER

|

Book Review: A Collection of Pieces by a Singular Patron of the Performing Arts By George Gelles

The Living Legacy of W. McNeil Lowry: Vision and Voice; Frank Kessel, editor; Peter Lang Publishing, New York; 502 Pages

Recalling Mac Lowry, encomiums abound.

During a stellar career spanning more than two decades, W. McNeil Lowry headed the Ford Foundation’s education program; launched a seminal program in support of the performing arts that still is acknowledged for its landmark significance; and became the Foundation’s Vice President for Humanities and the Arts.

As The New York Times aptly noted, he “helped make the Ford Foundation America’s largest non-governmental arts patron.”

Lincoln Kirstein, co-founder with George Balanchine of the School of American Ballet and of the early iterations of classical dance troupes that evolved into today’s New York City Ballet, praised Lowry as “the single most influential patron of the performing arts that the American democratic system has produced.”

And the current Ford Foundation president, Darren Walker, has stated that, “In the second half of the twentieth century, few people did more to influence and advance the arts in the United States than W. McNeil Lowry.”

A newsman by background, Mac edited the Cox Corporation’s daily in Dayton, Ohio, and then went to Washington to oversee the extensive Cox chain. He then served as associate director of the International Press Institute in Zurich, and in 1953 joined the Ford Foundation to head its education program.

A Jayhawk with a journalist’s curiosity and a polymath’s inclinations, Mac was true to his Kansan roots, suggesting that “… the fact that I was born 80 miles from the exact geographical center of the United States has given the foundation’s program a grass-roots approach.”

This essential collection of 47 pieces—speeches, research reports, essays and articles—was assembled by Frank Kessel, whose distinguished career has embraced issues of public policy in social science and the humanities. It allows us to share the breadth and depth of Mac’s passions.

Kessel cites Mac’s “radical imagination and meticulous care for the arts”, and these qualities are everywhere apparent—in his statements to Congress concerning the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities; in his personal salutes to heroes of regional theater, Zelda Fichandler and Nina Vance, miracle workers (with Mac’s guidance and support) in Washington, D.C., and Houston; in his generous public acknowledgments of milestone achievements of various institutions of professional training, a topic always dear to him, including the Juilliard School and the Minneapolis School of Art; and in his many implorations for a more enlightened and inclusive national policy for the arts.

Mac intuitively grasped the centrality of a vibrant culture to society’s health, a culture in which the performing arts would be admired not for their extrinsic values but prized for the creativity at their core. Among the values he deplored were the use of the performing arts as expressions of national purpose; as instruments of image-building on levels local, national and international; as spurs to economic activity; and as pro forma parts of a liberal education.

While these elements might bring ancillary benefits to the artistic enterprise, patronage of the arts—indeed true appreciation of the arts, and concomitant support from philanthropic sources and the public alike—must honor the artist for her- or himself.

Mac then suggested a notion as strikingly simple as it is rarely articulated: “Basically, it means accepting the artists and the arts on their own terms.”

He continued: “This does not appear to be a very unorthodox requirement when we consider how easily (in the main) philanthropy accepts, say, scientists or educators on their own terms. But individual patrons, corporations, public officials, and until recently foundations have too frequently chosen to concern themselves with the educational or social uses of the arts, if they have indeed devoted their resources to the arts at all.”

Written in 1962, Mac’s words still resonate.

He again expressed these views in 1977, in “The Performing Arts and American Society: The Past Twenty Years”. This was his Introduction to the 53rd convocation of The American Assembly, the occasional series of meetings hosted by Columbia University. Since its founding in 1950 by former President Eisenhower, who then was the university’s president, the organization historically examined broad issues of public policy, including the nature of democratic institutions and issues of the environment, world hunger and technology.

Addressing the arts was an American Assembly first. As described by Clifford Nelson, then president of the group, the conclave “brought together…a group of sixty-one Americans—performers, trustees, critics, directors, managers, and teachers from the worlds of ballet, modern dance, opera, theater, and symphony—to discuss The Future of the Performing Arts.”

Mac’s role was central: He invited the participants and he set the agenda. I had a privileged vantage point. Having months earlier joined the Foundation as part of the team designing “The City at 42nd Street”, the Foundation’s idealistic reimagining of the once-storied but then-shabby stretch of 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, I soon joined the Office of the Arts to work with Mac and his exceptional program officers: Marcia Thompson, Ruth Mayleas and Dick Sheldon, whose portfolios were dance, theater and music, respectively. (See “The Rise and Fall of ‘The City at 42nd Street’ by George Gelles”)

One day Mac called me over to talk about the American Assembly. Having worked on two similar initiatives, I anticipated a meeting full of promise. He explained that conversations among Assembly participants would take case studies as their points of departure, essays that examined symphony orchestras, opera companies, theater, modern dance and ballet. And he invited me to write the case study on ballet.

This would be a profile of the Pennsylvania Ballet and its director Barbara Weisberger, who enjoyed a long-standing relationship with both George Balanchine—in 1935, at age 8, she was the first child student of the great choreographer—and the Ford Foundation. Over the course of the weekend conclave, it became evident that these more than five dozen professionals could have been recruited only by Mac.

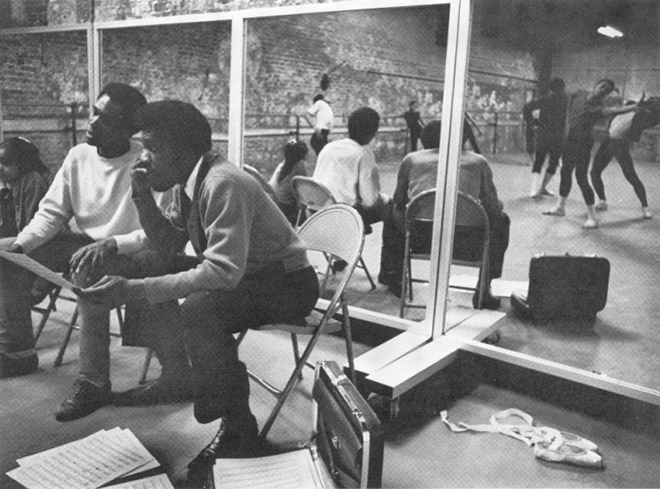

Notable was Mac’s advocacy of Black performing arts and artists. The Dance Theater of Harlem was a beneficiary of Ford support. It was founded by Arthur Mitchell, the first Black principal dancer in the New York City Ballet.

Equally esteemed, the Negro Ensemble Company was founded with Ford support. Led by eminent actor-playwright Douglas Turner Ward and actor-activist Robert Hooks, the company would nurture Black actors, including Phylicia Rashad, Denzel Washington, Samuel L. Jackson and Laurence Fishburne, and Black playwrights, among them August Wilson and Charles Fuller. Both companies still thrive today.

In the decades since Mac’s achievements, philanthropy’s face and focus have changed. The embrace and support of varied ethnicities, long overdue, is central to the foundation mission, and not only to Ford’s.

And foundations such as Ford recently have seen their activities complemented by individual philanthropies, among them the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, whose primary interests include world health care and women’s health and empowerment; Bloomberg Philanthropies (medical research, education and the arts); and Marc Benioff’s Salesforce Foundation (health care, the environment and issues of social justice).

No Maecenas has yet appeared who marries Mac’s deep sympathies for the performing arts with access to significant financial resources. In truth, the performing arts nowadays are languishing, experiencing, even before the Covid-19 pandemic, existential worries about sustainability in an environment that can seem indifferent.

In troubled times such as ours, I often turn to a sentiment offered by Katherine Anne Porter in a preface she wrote for the 1935 Modern Library edition of Flowering Judas and Other Stories. It is a sentiment I feel sure Mac Lowry would share:

“The arts do live continuously, and they live literally by faith; their names and their shapes and their uses and their basic meanings survive unchanged in all that matters through times of interruption, diminishment, neglect; they outlive governments and creeds and the societies, even the very civilization that produced them. They cannot be destroyed altogether because they represent the substance of faith and the only reality. They are what we find again when the ruins are cleared away.”

|