NEWSLETTER

|

“Saving America’s Cities”: A “Deep Dive” into the Life of Ed Logue By Thomas Seessel

Beginning in the mid-20th Century, Edward J. “Ed” Logue was acclaimed the savior of American cities. The Washington Post called him America’s “master rebuilder”.

Others condemned Logue. Author and activist Jane Jacobs said of Logue’s plans, “I thought they were awful and I thought he was a very destructive man.”

Lizabeth Cohen, professor of American Studies at Harvard University, finds the middle ground between these extreme views in her absorbing, balanced and readable account of Logue’s life and work in her 2019 book, Saving America’s Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age.

Cohen began work on it five years after Logue’s sudden death, at the age of 78, in 2000, and it took 15 years to complete.

What Cohen accurately calls her “deep dive” into Logue’s career expands our understanding of the many daunting difficulties of making American cities more livable and more equitable. Cohen also reminds us that we have an unsolved affordable housing crisis: reflecting costs that have risen faster than incomes. The percentage of renters who paid more than 30 percent of their incomes for housing has doubled since Logue’s time. And, 1.4 million people—including 147,000 families with children—used a shelter at some point in 2016.

Logue was born in Philadelphia, the oldest of five children in a staunchly Democratic, Irish-Catholic family. His father, a city tax assessor, died during the Depression, when Ed was 13. Logue recalled his home as “being without any racial prejudice”.

An unwavering New Dealer, who today might be called a social democrat, Logue was passionate about full equality for African-Americans. In his first publication, a book review of Robert Weaver’s Negro Labor, in the left-wing magazine The Progressive in 1946, Logue called for government action to deliver justice to African-American workers “now not soon”.

Logue went to Yale University on a scholarship in 1938 and found himself in a minority among a student body consisting largely of WASPs and offspring of Yale alumni. His freshman year, working part time in a campus dining hall, Logue led his fellow employees out on strike to protest low wages and poor working conditions. The strike ended with Yale’s recognition of its first union and a contract.

Describing himself as a “rebel in the belly of the establishment beast”, Logue married the daughter of the dean of Yale College and, later, led a hospital workers’ strike while his mother-in-law was a patient in the operating room.

Cohen divides her book into three parts, one for each of the major components of Logue’s career: New Haven (1954-’60), Boston (1960-’68) and the New York State Urban Development Corporation (1968-’75). A short coda covers Logue’s fourth major assignment, heading up New York City’s South Bronx Development Office (1980-’85).

Each part contains descriptions of Logue’s projects, tracing their evolution from concept to reality (or, in more than a few cases, non-starters). Fascinating attention is given to the often byzantine political maneuvering accompanying many of Logue’s ventures.

New Haven, an old industrial city, had been losing manufacturing jobs, and many of its residents were attracted to the burgeoning suburbs featuring housing and highways financed with federal funds. New Haven’s reform-oriented mayor, Richard C. Lee, hired Logue in 1954 as the city’s first development administrator and empowered him by consolidating planning and building functions under his control. While Logue was development administrator, New Haven was the recipient of more federal urban renewal funds per capita than any other American city.

Lee and Logue’s renewal strategy was guided by a vision of how the city could compete with the suburbs and retain middle-class residents and retail shopping. One of the earliest projects involved large-scale clearance of low-income, mainly black residential areas to make way for an expressway to connect the new interstate highway with downtown.

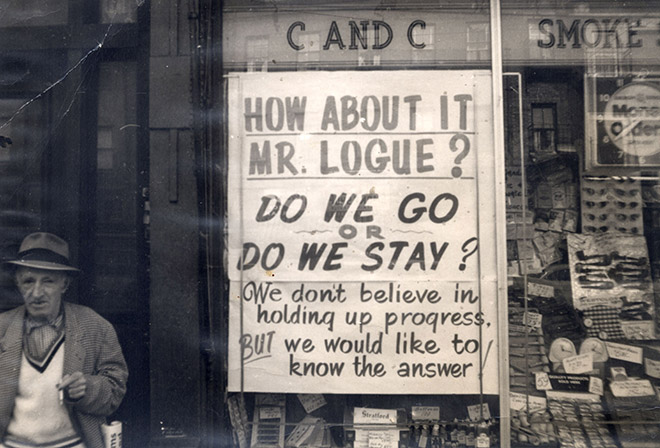

James Baldwin’s term for urban renewal, “Negro Removal”, contained more than a little truth. Urban renewal law required relocation of residents and businesses uprooted from demolished structures. Cohen discusses in detail the many obstacles Logue encountered in his attempts to find suitable replacement housing for African-Americans, in New Haven and Boston, including paucity of federal funding and neighborhood opposition to integration.

Logue insisted on high-quality architecture. He brought to New Haven, and later Boston and New York State, what Cohen describes as a “who’s who of modernist designers”, including Edward Larrabee Barnes, Marcel Breuer, Gordon Bunshaft, Philip Johnson, Louis Kahn, Kevin Roche, Paul Rudolph, Eero Saarinen, Mies van der Rohe and I.M. Pei. He chose them in part because he felt that excellent design of public housing would lessen its stigma.

Logue’s largest New Haven project was removal of a 12-acre swath of the central business district to enable construction of a 165,000-square foot indoor shopping mall, known as Chapel Square, anchored by two department stores and with a two-block long parking garage with 1,250 spaces. Strategically intended to compete with suburban malls, Chapel Square failed after about 30 years and was converted into apartments.

Logue decided that New Haven needed a “social renewal” companion program for urban renewal. In the late 1950s, he was in touch with the Ford Foundation’s director of public affairs, Paul Ylvisaker, who had won the reluctant support of Ford’s Board of Trustees for a major new initiative, the Gray Areas Program, to combat inner-city poverty.

New Haven, through a new nonprofit, Community Progress, Inc. (CPI), received a total of $5 million from Ford’s Gray Areas Program (about $40 million today). Logue and Mayor Richard Lee attracted the head of Connecticut’s AFL-CIO, Mitchell (“Mike”) Sviridoff, to head the new organization. Sviridoff went on in 1970 to become Ford’s vice president for national affairs. (Disclosure: The author worked at CPI from 1964 to 1967.)

Cohen writes that this was not Logue’s first collaboration with the Ford Foundation. In the early 1950s, before he began his job in New Haven, Logue served as special assistant to the United States ambassador to India. While there, he showed great interest in the Foundation’s community development activity, initiated by Ford’s representative, Douglas Ensminger, in poor areas of the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. After Logue returned to Connecticut, Ensminger enlisted him onto Ford’s Advisory Committee on Community Development for Calcutta, on which Paul Ylvisaker also served as a member.

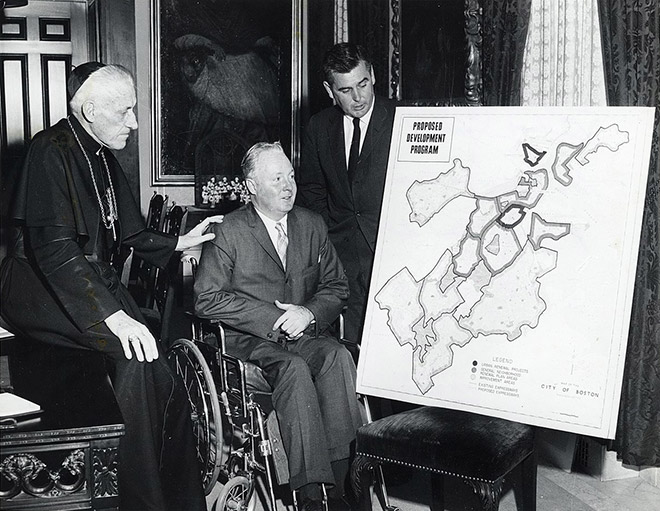

Logue was recruited to Boston in 1960 by another newly elected reform mayor, John Collins. Cohen writes that Logue, when he assumed his post in Boston, adopted as his theme “Planning With People”, and he embraced neighborhood preservation and rehabilitation, telling audiences that his new goal was “rehab, don’t demolish”. Logue convinced Ylvisaker to fund a social renewal program in Boston, known as ABCD, which received about $3.4 million.

As in New Haven, Logue began his tenure with a large-scale, visible project that removed an economically depressed eyesore: demolition of more than a thousand 18th and 19th Century buildings on 60 acres, and displacement of hundreds of residents, in historic but seedy Scollay Square. In its place arose a massive Government Center with a new Boston City Hall as its centerpiece. Logue’s strategy—public investment would be a catalyst for new private investment—was successful, according to Cohen: The total assessed value of taxable property increased by about 60 percent, and the number of people employed in the district more than tripled.

Logue followed through on his pledge to rehabilitate and repurpose historic structures where possible. Examples cited by Cohen are the historic Faneuil Hall, the old Boston City Hall and Quincy Market. The New York Times architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable lauded these as “stellar features of Boston’s exemplary downtown renewal, a remarkably sensitive synthesis of new and old…”.

Logue’s third big job was heading the New York State Urban Development Corporation (UDC), formed by Governor Nelson Rockefeller in the weeks following Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in 1968 to create low-income housing. The UDC was given extraordinary statewide powers to override local zoning and building codes, condemn and seize property through eminent domain, and create new financing schemes to carry out its mission.

Cohen writes that Logue’s UDC succeeded, in seven years, in building 117 developments in 49 cities and towns, 33,000 dwelling units for 100,000 people, about a third of them low-income, and 69 commercial, industrial and civic projects.

The remarkable record in housing was accomplished partly because of Logue’s use of his vast powers to “fast-track” developments, shortening the time from plans to completion from 5 to 6 years to as little as 18 months. In an interview, UDC’s chief architect, Ted Liebman, told Cohen that, “Every 10 minutes there would be a groundbreaking and Ed Logue would say, ‘Why aren’t we doing more? We don’t need housing anymore?’”

Cohen relates how the UDC transformed Roosevelt Island, a nearly abandoned sliver of 147 acres in New York City’s East River, formerly known as Welfare Island and dedicated to the care of “the diseased, the criminal, the impoverished, and the otherwise undesirable of New York City”. One of three “new towns” developed by the UDC, Roosevelt Island, which is visible from the Ford Foundation, today is home to about 14,000 people, parks, shops and Cornell Tech, a new science-focused graduate school built where a hospital used to stand.

The UDC’s default on bond obligations in 1975, which left many projects unfinished, occurred when New York State was in the midst of more enveloping fiscal problems. A scapegoat was needed by the new governor, Hugh Carey, a Democrat, who blamed the UDC’s problems on Logue’s mismanagement, a charge that never found legs in subsequent investigations.

Cohen puts the implosion of UDC in context: In 1973, President Nixon had frozen federal housing subsidy funds, the lifeblood of many of UDC’s projects. The following year, Logue lost his political support when Governor Rockefeller resigned to become vice president. Soon after taking office as governor in 1975, Carey asked for Logue’s resignation.

The final installment of Cohen’s superb account focuses on Logue’s work on a smaller scale, when he was appointed by Mayor Ed Koch as director of New York City’s South Bronx Development Office (SBDO) in 1980. Working with local nonprofit community development corporations, SBDO identified a redevelopment site, Charlotte Street, that had come to epitomize urban deterioration when President Jimmy Carter called it “the worst slum in America” after he visited the area in 1977.

After five years of effort, the SBDO succeeded in building 92 single-family ranch houses in the area re-christened Charlotte Gardens. The Ford Foundation gave the project $300,000 through its offshoot nonprofit, the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), headed by Logue’s long-time collaborator, Mike Sviridoff.

When the Charlotte Gardens pre-fab homes went on sale, in the mid-1980s, for an average of about $60,000, there were 600 applicants, about 90 percent of whom were South Bronx residents. In 2009, CNN said that the average home values had increased tenfold in 14 years, and called the project “a slice of suburbia in one of the country's most urban—and poor—counties [and] one of the greatest real estate turnarounds ever”.

In conclusion, Cohen finds that “some of Logue’s work improved the cities and neighborhoods he worked in, others did not.” She sums up Logue’s career this way: “At times, Logue was a figure of Greek tragedy, whose good intentions were undermined by his own fatal flaws….Eager to achieve greater social and economic opportunity…he became deeply invested in an expert-driven activist government.…[H]e sometimes paid mere lip service to community input, sanctioning a less-than-democratic process that marginalized and alienated the very people whose lives he set out to improve.”

Tom Seessel was a program officer in the Ford Foundation’s Urban and Metropolitan Development office from 1970 to 1974, and a consultant in the Office of the President from 2002 to 2009.

|